The Work vs. The Job

The subtle but critical difference between team members who follow job descriptions versus those who understand their role's true purpose.

I’ve been thinking about a distinction that keeps surfacing in my leadership conversations—the difference between team members who “do the work” versus those who “do the job.”

The difference is subtle, but can completely change the dynamic of a team.

Those who “do the work” execute their job description to the letter. They complete assigned tasks, follow procedures, and meet expectations. Those who “do the job” understand the nuance of their role and account for the broader context of what needs to happen.

The Research Confirms It

This isn’t just a management theory or a “feeling” that you may have.

Organizational psychology has studied this phenomenon extensively for decades through what researchers call Organizational Citizenship Behavior—discretionary behaviors that go beyond formal job requirements but contribute to organizational effectiveness.

The research shows that OCB involves “individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization”. In simpler terms: the stuff that matters but isn’t written down.

Studies on role breadth self-efficacy reveal that some employees naturally interpret their roles broadly—seeing their job as “anything that helps the team or company succeed”—while others maintain narrow boundaries limited to prescribed tasks.

The distinction shows up in discretionary effort research too. Discretionary effort is defined as “the level of effort people could give if they wanted to, but above and beyond the minimum required”. The key insight? Emotional commitment drives far greater improvements in performance than rational commitment alone.

The Leadership Challenge

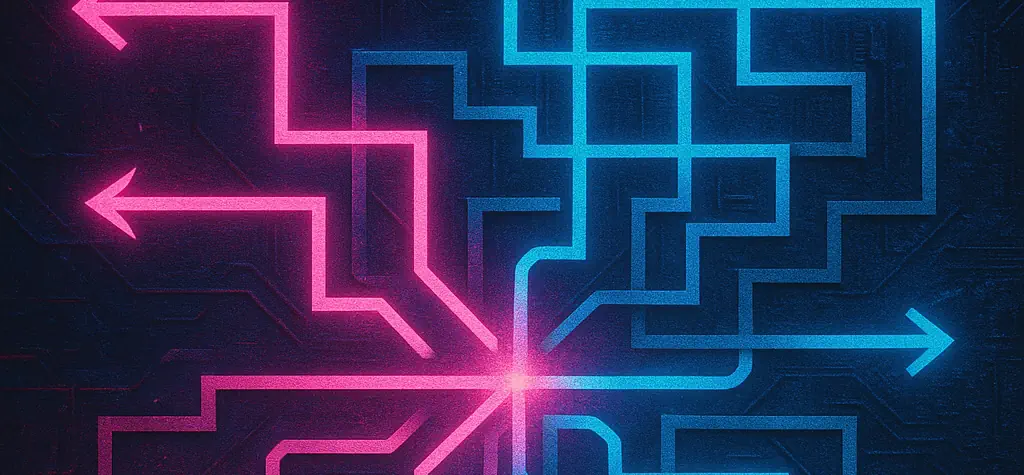

As leaders, we desperately want teams that “do the job”—people who understand context, anticipate needs, and contribute beyond their formal scope. But we face constant pushback: “That’s not in my job description.”

This tension isn’t arbitrary resistance. Research on “job creep” shows what happens when extra-role behaviors gradually become expected rather than appreciated. When discretionary actions slowly transform from voluntary contributions to mandatory expectations, employees begin feeling pressured to continuously expand their scope without additional recognition or compensation.

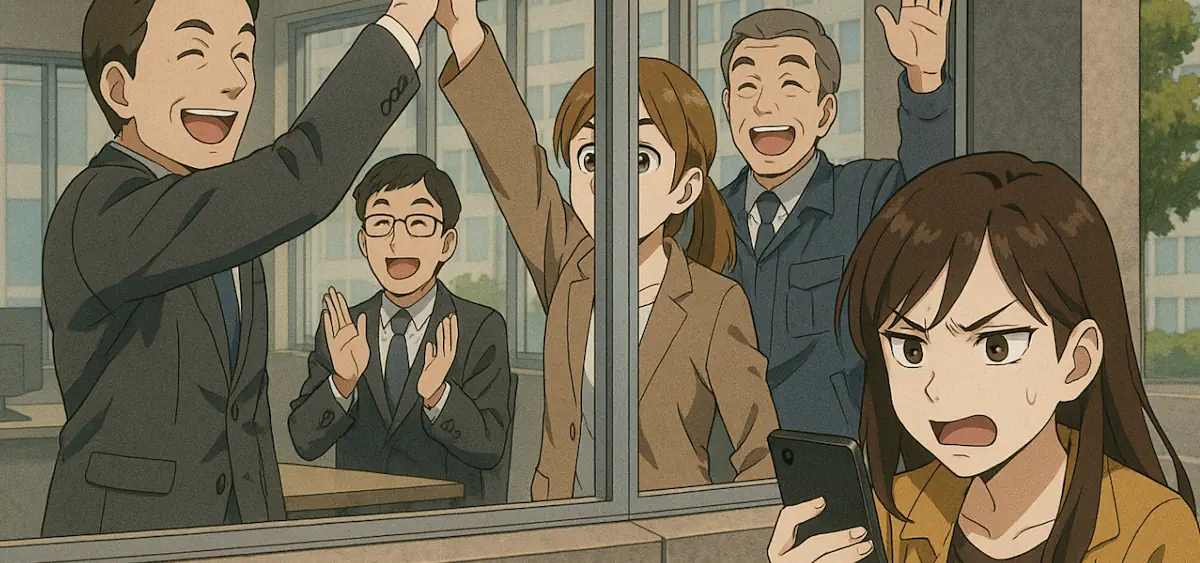

The result? Organizations end up with employees working “50, 60, 70 hours a week” as “above and beyond became what just needs to happen”. What started as voluntary contribution becomes mandatory overload.

The cost isn’t just individual burnout. When role boundaries dissolve without structure, high performers carry the load while others retreat further into task compliance. It also traps the high performer as it becomes increasing difficult to justify change because the work’s “getting done.”

Sometimes, the only way to force change is to drop one of those spinning plates.

The Uncomfortable Reality

I’ve observed (and lived) this pattern a few times in my career. The people who naturally “do the job” often become the go-to solution for everything that falls between formal roles. They see what needs doing and do it. Meanwhile, those who “do the work” maintain their boundaries and, frankly, often have better work-life balance.

Both approaches make sense from the individual’s perspective.

The “do the work” approach provides predictable scope, clear expectations, and protection from endless responsibility creep. The “do the job” approach offers growth opportunities, higher visibility, and often better long-term career outcomes—but at significant personal cost.

Role Breadth Spectrum

~25% of employees

• Task-focused

• Clear boundaries

• Job description adherence

~50% of employees

• Selective helping

• Context-dependent

• Situational contribution

~25% of employees

• Proactive helping

• Organizational thinking

• Consistent discretionary effort

What This Means for Leaders

As leaders, we’re caught in the middle of competing organizational needs. We need the flexibility and adaptability that comes from people who “do the job.” But we also need sustainable, scalable operations that don’t depend on a few individuals carrying disproportionate loads.

The research suggests this isn’t a problem we can motivate our way out of. Studies show that discretionary work effort is influenced more by working conditions, social context, and organizational culture than by individual personality traits. Coming from my experience transitioning from technology to product, I’ve seen how the same person can shift between these approaches based entirely on environment and expectations.

The question isn’t how to get everyone to “do the job”—that’s neither realistic nor necessarily healthy. The question is how to create systems and cultures where the right people can contribute broadly without burning out, while ensuring essential work gets done regardless of individual interpretation.

“The art of leadership is saying no, not yes. It is very easy to say yes.”

— Tony Blair

The Ongoing Tension

This distinction will persist because it reflects a fundamental tension in organizational life: the need for both structure and flexibility, both reliability and adaptability.

Some roles genuinely require people who “do the job”—positions where context, judgment, and initiative matter more than task execution. Other roles work better with people who “do the work”—where consistency, compliance, and predictability are paramount.

The leadership challenge isn’t resolving this tension but managing it thoughtfully. Recognizing that both approaches serve organizational needs. Understanding which roles require which mindset. And most importantly, being honest about the true scope of what we’re asking from our teams.

What’s the last role you hired for that really needed someone who would “do the job,” but you only described “the work” in the job posting?