I Don't Google Things Anymore

How AI tools changed the way I find and use information

Somewhere in the past year, I stopped googling things. Not entirely, but enough that I noticed the shift. When I need to understand something now, my default is Perplexity or Claude, not a search engine. At home, it’s even more organic as I just “ask the home” my question and Gemini and I have a conversation on the spot.

This isn’t about Google getting worse (though the SEO and sponsored link spam problem is real). It’s about what I actually need from information retrieval changing.

The Problem With Ten Blue Links

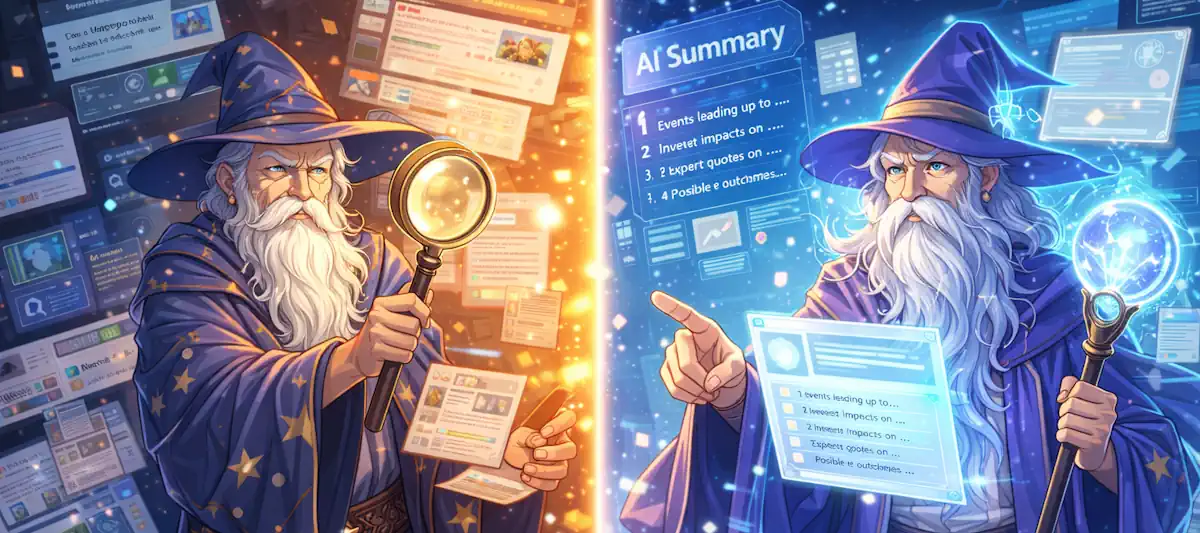

Traditional search gives you a list of documents that might contain your answer. You click through, scan, evaluate credibility, synthesize across sources, and eventually form a conclusion. The search engine’s job ends at delivering ranked links. The thinking remains entirely yours.

That model worked when the internet was smaller and the signal-to-noise ratio was better. Now I search for something straightforward and wade through affiliate content, SEO-optimized filler, articles that bury the actual answer under paragraphs of backstory, and ads disguised as organic results. Nearly 60% of Google searches now end without a click because users either find their answer in a snippet or give up.

The ten blue links model assumes I want to do the correlation work myself. Increasingly, I don’t. I want the correlation done for me, with sources I can verify if needed.

What Changed in How I Search

The shift happened gradually, then all at once. A few patterns emerged.

From fixed queries to dynamic conversations. Google trained me to craft the perfect query upfront. If the results weren’t right, I’d refine keywords and try again. AI tools let me start with an imperfect question and iterate. “What’s the best approach for X?” becomes “Actually, I should mention we have constraint Y” becomes “How does that change if Z is also true?” The search evolves with my understanding of what I’m actually asking.

From retrieving documents to getting analysis. When I ask Perplexity about market trends, I don’t get a list of articles about market trends. I get a synthesis of what multiple sources say, with inline citations so I can verify specific claims. The tool did the work I used to do manually: read multiple sources and identify where they agree or disagree.

From single answers to adjusted parameters. I’m no longer stuck asking “what’s a good cake recipe” and getting one fixed result. I can ask for a recipe, then adjust: “I don’t have buttermilk, what can I substitute?” “Make it work for high altitude.” “Scale it down by a third.” The answer adapts to my actual constraints in real time.

The Search Evolution

Reducing Signal to Noise

The real value isn’t just speed, but noise reduction.

When I researched a technical topic last month using traditional search, I got results from vendor blogs pushing their products, outdated Stack Overflow threads from 2019, content farms rehashing the same surface-level information, and maybe two actually relevant sources buried on page two. Finding signal required filtering through significant noise.

The same query in Perplexity surfaced the relevant technical documentation and recent discussion threads, with citations to primary sources so I could verify the synthesis. Not perfect, but the noise floor was dramatically lower. What’s even better is being able to dig into counterpoints and better understand both sides of the data–as a human, I may not always have the context to do that.

This matters because attention is finite. Every minute spent evaluating whether a source is worth reading is a minute not spent on the actual problem. AI tools shift the verification burden from “is this source worth my time?” to “does this synthesis match what the cited sources actually say?” The second question is faster to answer.

Where Google Still Wins

I haven’t abandoned Google entirely. It still does some things better, though their integration with Gemini blurs the line.

Navigational queries. When I just need to get to a specific website, Google is faster. “GitHub login” doesn’t need AI synthesis (yes, you know you do this too… don’t deny it).

Current structured data. Stock prices, sports scores, weather, store hours. Google surfaces this instantly in ways that AI tools still struggle to match consistently.

The pattern: Google excels at retrieving known information from known sources. AI tools excel at synthesizing unknown information across multiple sources. Different jobs.

The Trust Question

The shift from search to synthesis changes who does the thinking.

Traditional search made the synthesis work visible. I could see the sources, evaluate them independently, and form my own conclusion. The search engine was just a librarian pointing me to shelves. I’m old enough to remember printing off my sources at the library to go sit in the corner and comb through them, annotate, and cite in my research papers.

AI tools hide that process. I get a confident summary, and unless I click through citations, I’m trusting the model’s judgment about what sources matter and how to weight them. That’s a different relationship with information.

Research suggests that nearly half of users don’t verify AI-generated information if it “sounds right.” I understand the temptation. The summaries are well-written and confident. Clicking through to verify feels like extra work.

But confidence isn’t accuracy. I’ve caught errors often enough that verification stays part of my workflow.

The Blur Between Search and Generation

There’s something philosophically interesting happening that I don’t think we’ve fully grappled with yet.

Traditional search retrieves existing information. AI tools generate new text based on patterns in existing information. When I ask for a synthesis of market trends, am I retrieving what analysts have said, or am I generating a new document that happens to be informed by what analysts have said?

The answer is probably “both,” and that’s uncomfortable. We’re used to a clear line between finding information and creating information. These tools blur that line in ways that change what it means to “research” something, and, from an academic perspective, it changes what it means to “cite” something.

I don’t have an answer to this. I just notice that my relationship with information provenance has gotten more complicated, and I’m not sure the tools have caught up with helping me navigate that complexity.

Where This Is Going

Google still handles nearly 90% of search traffic, but the trajectory seems clear. AI Overviews now appear in roughly half of Google searches. Perplexity’s traffic grew over 240% year-over-year. The behavior shift is real, especially among younger users and technical professionals.

My prediction: within five years, the default expectation for “search” will be synthesis, not links. We’ll still need to navigate to specific sites and complete transactions. But for understanding things? The ten blue links model will feel as dated as card catalogs.

The question isn’t whether AI will change how we find information. It already has. The question is whether we’ll develop the verification habits and critical thinking skills that the new model requires.

For now, I’m treating this as a tool upgrade, not a replacement for judgment. AI search reduces the time between question and understanding. It doesn’t reduce the need to think critically about what I find. If anything, the confidence of the outputs makes that critical thinking more important, not less.

The cake recipe example keeps coming back to me. I’m not stuck with one fixed answer anymore. I can adjust the question until I get something that fits my actual situation. That’s genuinely useful, but I still have to taste the cake before I serve it.