Are We Doing Good? Wrong Question

Why asking yourselves misses the point entirely

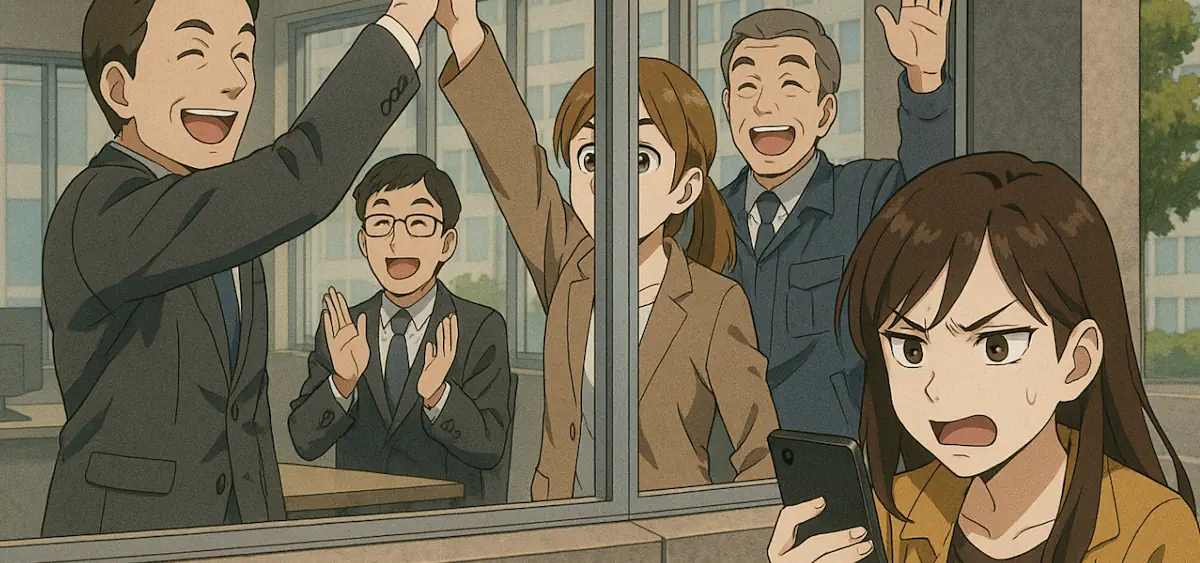

A team gathered to discuss their latest feature release and someone asked: “Are we doing good?”

The room turned inward. Discussions around code quality, interaction patterns, velocity, and training. Everyone had an answer about craft, effort, and execution quality.

Nobody mentioned customers.

My push? Candor and clarity: “That’s the wrong question. We shouldn’t ask ourselves if we’re doing good—we should ask our customers if we’re delivering value to them.”

The distinction reveals a dangerous gap between internal pride and external value. When teams default to self-assessment, they’re really asking “did we execute well?” That’s not the same as “did we solve a problem worth solving?” One question keeps you comfortable. The other one keeps you in business.

The Comfort of Internal Validation

Teams naturally gravitate toward self-assessment because it’s comfortable. We control the criteria. We know the constraints. We understand the technical challenges that make this “pretty good, actually.”

Harvard Business Review research found that while employees believed strategic alignment within their companies was 82%, actual alignment based on their descriptions of company strategy was only 23%—nearly four times lower than perceived. We think we’re aligned with customer needs because we’ve aligned with each other.

I’ve watched this pattern play out before. Teams ship technically excellent solutions that customers barely use. The code is clean. The architecture is sound. The deployment went smoothly. But customers don’t care about any of that—they care whether it solves their actual problems.

In public education, we built a beautiful attendance tracking system. Teachers praised the interface design. Administrators loved the reporting features. We felt great about the quality of our work.

Then we noticed something: attendance hadn’t improved. The system tracked absences efficiently, but it didn’t help anyone address the underlying reasons students were missing school. We’d optimized for tracking instead of solving the real problem—keeping students engaged and in class.

We were doing good work. We weren’t delivering good value.

What “Good” Actually Means

The fundamental problem with asking ourselves is that we’re answering the wrong question with the wrong definition.

Internal good focuses on:

- Technical quality and craftsmanship

- Meeting our own standards

- Executing according to our processes

- Delivering what we committed to build

Customer-defined good focuses on:

- Whether it solves their actual problem

- If they’d recommend it to colleagues

- How it changes their daily work

- Whether they’d pay more for it

These aren’t the same thing. Not even close.

Consider an ordering system. The engineering team had built something technically flawless—perfect data validation, robust error handling, zero bugs in production. They were rightfully proud of the quality.

But customers abandoned it halfway through nearly 60% of the time. The system asked them to make seventeen decisions before confirming an order. Each decision was logically necessary from a technical standpoint. But the cumulative cognitive load—the mental effort required to process all those choices—overwhelmed users.

As I’ve written about cognitive load, working memory can effectively handle about 7±2 pieces of information simultaneously. When we exceed this capacity, performance degrades rapidly. This ordering system demanded users track order details, pricing variations, delivery options, account settings, and payment information all at once.

The team measured success by code quality and system reliability. Customers measured success by “can I order without thinking too hard about it?” The system worked perfectly. Customers chose competitors with simpler flows.

Internal vs. External Success Criteria

• Story points completed

• Bug count and severity

• Deployment frequency

• Design system compliance

• Sprint velocity trends

• Problems actually solved

• Reduction in frustration

• Business outcomes achieved

• Willingness to recommend

• Continued usage patterns

Both matter. But only one determines product success.

Customer validation is about testing assumptions through actual customer feedback and data, minimizing the risk of building something customers don’t want or need. When we skip this step and rely on internal validation alone, we’re essentially building in the dark while congratulating ourselves on our excellent flashlight technique.

Why Teams Default to Self-Assessment

There are good reasons teams ask themselves instead of customers. Understanding these helps us break the pattern.

Speed feels faster. Internal validation happens immediately. Customer validation takes time—scheduling conversations, analyzing feedback, synthesizing insights. When you’re under pressure to ship, asking the team feels efficient.

Except it’s not. Intergiro, a Swedish fintech company, embedded surveys directly into their product and increased user engagement by 54% while accelerating feature validation by 50%. Customer validation done right actually speeds up the right work—and prevents wasting time on the wrong work.

Expertise creates confidence. We’re the experts. We’ve studied the domain. We know the technology. We’ve built similar features before. Surely we can assess quality ourselves.

But expertise in execution doesn’t equal expertise in value delivery. I’ve been a CTO. I’ve led engineering teams. I know how to build technically excellent systems. That knowledge doesn’t tell me whether customers will find those systems valuable in their actual workflows.

Criticism is uncomfortable. Customer feedback can be brutal. They don’t understand the constraints. They don’t appreciate the technical challenges. They want things that seem impossible or unreasonable.

True. And that discomfort is exactly the signal we need. According to Prosci research, 40% of respondents identified lack of alignment on goals and objectives as the main reason change success was not defined for their projects. When we avoid customer feedback because it’s uncomfortable, we’re choosing comfortable failure over uncomfortable success.

The Definition Gap

Even when teams ask customers, they often ask the wrong questions or misinterpret the answers because they haven’t aligned on what “good” means.

I worked with a startup where the team celebrated shipping a feature ahead of schedule with zero bugs. They asked customers: “Does it work?” Customers said yes. Team declared success.

Three months later, usage metrics showed customers tried the feature once and never returned. The feature worked perfectly—it just didn’t solve a problem worth solving repeatedly.

The team had defined “good” as “functional and bug-free.” Customers defined “good” as “worth changing my workflow for.”

Prosci research found that among teams who measured compliance with change and overall performance, 76% met or exceeded project objectives, while only 24% of those who didn’t measure met objectives. But measuring the wrong things—like internal quality metrics instead of customer outcomes—gives you false confidence.

I’ve written before about how success needs clear definition upfront, especially in continuous delivery environments where “done” is a moving target. But even with clear internal success criteria, we still need external validation that we’re solving problems customers actually have.

Building Customer-Validation Habits

Here’s what I’ve seen work, based on watching teams shift from internal to external validation:

1. Change the default question

- Stop asking: “Are we doing good?”

- Start asking: “Are we delivering value customers recognize?”

This small language shift changes everything. The second question can’t be answered by looking inward. It forces you to talk to customers.

2. Separate quality from value

Quality is necessary but not sufficient. You need both technical excellence and customer value. Track them separately:

- Quality metrics: Code coverage, bug rates, performance benchmarks

- Value metrics: Usage patterns, time-to-value, customer satisfaction, willingness to recommend

When quality is high but value metrics are low, that’s your signal to stop and ask customers what’s missing.

3. Build feedback into the workflow

Companies that embed feedback programs into their long-term strategies ensure that customer input drives decision-making at every level, promoting a customer-centric culture that leads to sustained growth and loyalty.

Don’t make customer validation a special event. Make it automatic:

- Weekly customer conversations (not just when something breaks)

- In-product feedback mechanisms at key decision points

- Quarterly deep-dive sessions with different customer segments

- Post-release validation surveys at 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months

4. Close the loop publicly

When customer feedback changes your direction, tell your team and your customers. This reinforces that external validation matters more than internal consensus.

At one fintech company, we started sharing customer feedback in sprint reviews alongside our internal metrics. It was uncomfortable at first—customers didn’t care about our elegant architecture if the workflow still frustrated them. But this transparency shifted how teams thought about success.

When Internal and External Definitions Clash

The hard moments come when internal quality standards and external value perceptions conflict. You know you’ve built something technically excellent, but customers don’t seem to value it. What then?

I’ve seen three patterns:

Pattern 1: We’re right, they’re wrong Team doubles down on internal quality, assuming customers “don’t understand” the value yet. Sometimes this works—truly innovative solutions need time for adoption. Usually it doesn’t. You end up with a beautifully engineered solution nobody wants.

Pattern 2: Chase every customer request Team abandons internal standards and builds whatever customers ask for. This creates technical debt, inconsistent experiences, and products that satisfy individual requests while serving no one well. As I’ve written about understanding what customers need versus what they ask for, taking requests at face value misses the underlying problems worth solving.

Pattern 3: Negotiate the tension Teams use customer feedback to question their assumptions while maintaining technical standards that enable long-term value. This is the hardest path—and the only one that works consistently.

In aviation, we built decision support systems where safety was non-negotiable. We couldn’t compromise on validation or reliability just because pilots wanted faster response times. But pilot feedback revealed that our extensive validation process created cognitive load at critical moments. We didn’t abandon validation—we redesigned how we presented validated information to reduce that load.

Both internal quality and external value mattered. The tension between them made the product better.

The False Choice

Here’s what this isn’t about: choosing between craftsmanship and customer value.

Internal quality enables external value. As I explored in the difference between revolutionary and evolutionary innovation, sometimes breakthrough value requires accepting higher initial failure rates. But sustainable value requires technical excellence underneath.

The question isn’t quality OR value. It’s recognizing that quality is an input to value, not a substitute for it.

The Quality-Value Relationship

You need both. But if you have to choose where to start validation, start with customers. Technical quality can be improved. Customer indifference is much harder to overcome.

Making This Real

Theory is easy. Changing team habits is hard.

Start your retrospectives with customer feedback, not team metrics. Put actual customer quotes—positive and negative—on the board first. Then discuss internal execution. This reframes “good” in customer terms before discussing internal quality.

Change how you celebrate wins. Stop celebrating only on-time delivery or zero bugs. Start celebrating customer adoption, reduced support tickets, and positive customer outcomes. What you celebrate defines what teams optimize for.

Make customer conversations everyone’s job. Engineers, designers, and product managers should all talk to customers regularly. When the whole team hears customers directly, they can’t hide behind internal quality metrics.

Track the gap. Monitor both internal quality metrics and customer value metrics. When they diverge, that’s your most important conversation. Why do we think this is good, but customers don’t value it?

The Accountability Question

This gets uncomfortable: if customers define success, does that mean internal quality doesn’t matter? Are we just order-takers?

No, the distinction I’ve learned matters is that teams are accountable for both technical quality and customer value. But the weight is different.

- Quality is your professional responsibility. You don’t ship garbage just because customers asked for it quickly.

- Value is your job security. You can’t sustain a business on internal pride alone.

In fintech, we couldn’t compromise on calculation accuracy or security standards no matter what customers requested. But customer feedback revealed that our bulletproof validation was creating workflow friction that drove people to less secure alternatives.

- Our responsibility: maintain security standards.

- Our job: figure out how to do that without creating friction that pushes customers toward unsafe workarounds.

Customer feedback doesn’t override professional judgment—it informs where you need to apply that judgment.

The Three-Month Test

Want to know if your team defaults to internal or external validation?

Look at your last quarter’s worth of decisions. For each major feature or change, ask:

- What evidence did we use to validate this was the right thing to build?

- Where did that evidence come from—our team or our customers?

- How did we measure whether it succeeded?

If most of your evidence and success metrics are internal, you’re asking yourselves. If they’re external, you’re asking customers.

Smart product teams align customer feedback with their business goals, using it as a guide to refine the product roadmap, revealing blind spots and helping validate product decisions before sinking resources into development.

Neither extreme is perfect. Pure internal validation leads to building what you think is good. Pure external validation leads to having no cohesive vision. The balance lives somewhere in the 70-30 range—70% of your validation should come from customers, 30% from your internal expertise and vision.

What This Looks Like in Practice

A product team I worked with recently implemented what they call “assumption logging.” Before building anything, they write down:

- What we assume customers need

- Why we think this solution addresses that need

- How we’ll know if we’re right (customer-defined success metrics)

- How we’ll know we built it well (internal quality metrics)

Then they validate each critical assumption with customers before a single line of code is written. After shipping, they measure against both sets of criteria.

The first few times, nearly 60% of their assumptions were wrong and that’s fantastic! Customers cared about different problems or wanted different solutions. But because they checked before building, they saved months of work on features customers wouldn’t value.

Now their assumption validation rate is around 80%. Not because they got better at mind-reading—because they got better at asking customers what actually matters.

The Bottom Line

When your team gathers to discuss whether you’re doing good, pause. Recognize that question for what it is: a trap that keeps you looking inward when success is defined externally.

Ask instead: Are we delivering value our customers recognize and would pay for?

This question can’t be answered by looking at your test coverage, your sprint velocity, or your architectural elegance. It requires talking to the people whose problems you’re trying to solve.

Quality matters. Craftsmanship matters. Technical excellence matters. They just don’t matter enough if customers don’t value what you’ve built with all that quality and craftsmanship and excellence.

As I’ve explored in momentum over metrics, the best measures consider multiple dimensions—not just what we achieve, but how we achieve it and who we become along the way. The same principle applies here: measure both internal quality and external value. Just remember which one actually determines if your product succeeds.

Next time someone asks “are we doing good?” I hope you’ll respond: “I don’t know. Let’s ask our customers.”