What I've Learned Using AI for Customer Research

Months of using Claude, Perplexity, and Gemini to understand customers better

Earlier this year, I wrote about leveraging AI in product management with the enthusiasm of someone who’d just discovered a new set of power tools. Nine months later, I have a more nuanced view. The tools are genuinely useful, but not in the ways I initially expected.

I’ve spent this year using Claude, Perplexity, and Gemini for customer and segment research across multiple projects. Some of what I learned confirmed the hype. Most of it didn’t.

The Shift in How I Engage

The biggest change isn’t which tool I use. It’s how I think about the interaction itself.

In 2023, the conventional wisdom was highly structured prompts. Role assignments, explicit constraints, step-by-step instructions. “You are a market research analyst. Given the following context, provide a structured analysis with exactly five key findings.” That approach made sense for earlier models that needed scaffolding to stay on track.

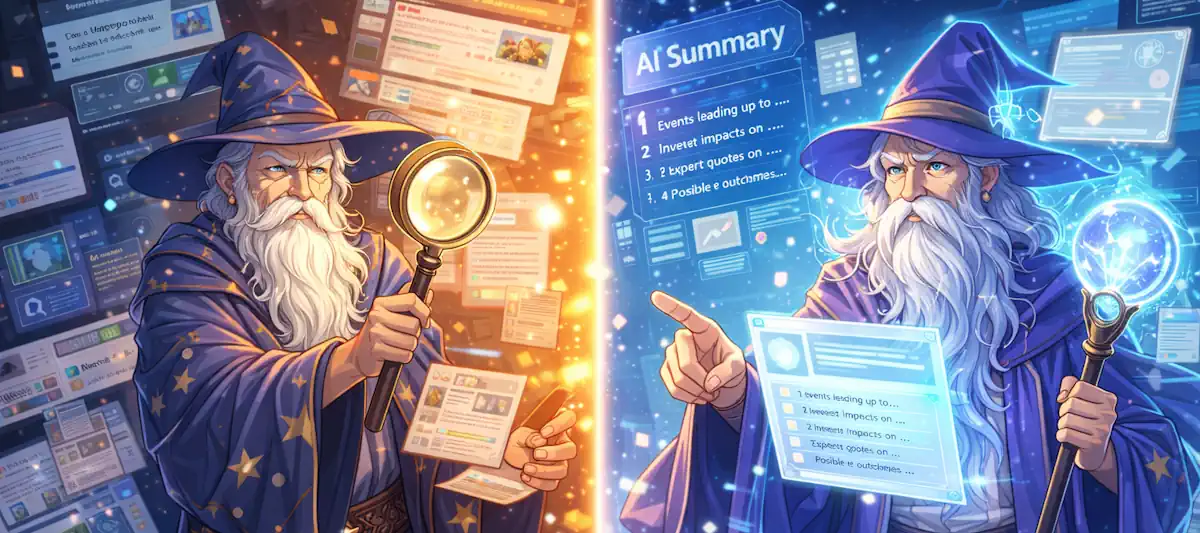

The newer reasoning and conversation models work differently. Research has started showing that overly structured prompts can actually constrain the deeper thinking these models are now capable of. The shift I had to make wasn’t from traditional search to AI queries. It was from treating AI as a command-line interface to treating it as a thinking partner.

Now I engage more humanistically. Instead of rigid structures, I provide context about what I’m actually trying to decide and why it matters. “I’m evaluating whether to add a self-service tier to an enterprise product. What patterns have emerged in companies that made this transition successfully versus those that struggled?” The framing is conversational, and the model has room to reason through the problem.

The other shift: moving from “tell me about a thing” to providing timelines, ranges, and parameters that let the tool do correlation work. Instead of asking for information, I ask for analysis across datasets. Find the outliers. Identify patterns over time. Compare these segments against those benchmarks. The tool becomes a data partner rather than a data source.

Where Each Tool Actually Excels

After rotating through these tools across different research tasks, I’ve developed preferences that don’t always match the marketing.

Perplexity became my default for competitive intelligence and trend validation. The inline citations matter more than I expected. When I’m preparing analysis for stakeholders, being able to say “according to [specific source]” rather than “AI told me” changes how the research lands. Perplexity now handles roughly 780 million queries monthly, and I understand why. For research where provenance matters, it’s the right tool.

Claude is where I do the actual thinking. Not research gathering, but synthesis and exploration. I’ll dump sanitized interview transcripts and anonymized survey responses into a project alongside competitive notes, then work through what the patterns might mean. The extended context window lets me have conversations that build on previous context without re-explaining everything. For customer research specifically, I use Claude to identify themes I might be missing in qualitative data.

Gemini surprised me. I initially dismissed it as “Google’s ChatGPT,” but it’s become useful for research that spans documents I already have in Google Workspace. When I need to cross-reference customer feedback in Drive with market data I’ve collected, Gemini’s integration saves the context-switching.

How I Actually Use Each Tool

What Doesn’t Work (Yet)

I’ve also learned where these tools fall short for customer research specifically.

Primary research still requires humans. I experimented with using AI to help generate interview questions, and the questions were technically fine but generically so. They lacked the follow-up instincts that come from actually knowing the domain. The AI couldn’t ask “wait, you mentioned compliance earlier—how does that connect to what you just said about pricing?” because it wasn’t in the room reading body language and hearing tone shifts.

Synthesis without validation is dangerous. This isn’t unique to AI. Any time we let a summary shape a decision without going back to source material, we risk missing crucial outliers. An aggregate view can be accurate on average while completely obscuring the segment that matters most. AI makes this temptation worse because the summaries sound so confident and complete. I’ve learned to treat AI synthesis as a starting point for investigation, not a conclusion.

The confidence problem is real. These tools present information with equal confidence whether they’re synthesizing well-documented research or hallucinating plausible-sounding nonsense. I’ve caught Perplexity citing sources that didn’t actually support the claim, and Claude confidently describing market dynamics that turned out to be outdated. Verification isn’t optional.

The Workflow That Emerged

After nine months of experimentation, I’ve landed on a research workflow that plays to each tool’s strengths while compensating for weaknesses.

Stage 1: Landscape mapping with Perplexity. Before diving into customer research, I use Perplexity to understand the current state of whatever market or segment I’m investigating. Who are the players? What are the recent developments? What do analysts say? The citations let me quickly validate whether the synthesis is trustworthy.

Stage 2: Primary research stays human. Interviews and surveys. Direct observation when possible. No AI shortcuts here. The nuance matters too much.

Stage 3: Pattern recognition with Claude. After I have primary data, I bring sanitized transcripts to Claude for help identifying themes I might be missing. “Here are transcripts from 12 customer interviews. What patterns do you notice that I should investigate further?” This isn’t asking Claude to draw conclusions. It’s asking for a second perspective on what questions to ask next.

Stage 4: Synthesis and pressure-testing. I write my own synthesis first, then use Claude to challenge it. “Here’s my hypothesis about why this segment struggles with adoption. What evidence from these transcripts supports or contradicts this?” The pushback is often useful, occasionally revealing blind spots in my reasoning.

What Changed in My Practice

The tools haven’t replaced customer research skills, but they’ve amplified certain activities while making others feel more optional than they should be.

I spend less time on initial literature review and competitive scanning. That time moved to deeper analysis of primary research, which is probably the right trade-off. I’m more systematic about documenting research conversations because I know I’ll want to feed them into Claude later. I’m also more skeptical of synthesized findings than I was before I understood how these tools actually work.

The Harvard Business Review reported in November that organizations are using AI to create “synthetic personas” that simulate customer responses. I’ve experimented with this. The simulations are useful for stress-testing messaging, but I wouldn’t trust them for discovering customer needs. They reflect the training data’s patterns, not the specific context (or fickleness) of your customers.

Still Learning

I’m learning every day and, many days, it feels like the tools keep evolving faster than my practices. ChatGPT added Deep Research, Perplexity expanded its capabilities, Claude improved its reasoning. Each update shifts what’s possible and what’s practical.

What I’m increasingly confident about: these tools make good researchers better and poor researchers more dangerous. They accelerate whatever research instincts you already have. If you know what questions to ask and how to validate answers, AI multiplies your effectiveness. If you don’t, it multiplies your confidence without improving your accuracy.

The nine-month version of me using these tools looks different from the beginner who wrote that March post. I expect the version a year from now will look different again.

For now, my approach is simple: use AI to expand what you can investigate, not to replace your judgment about what you find. The tools are genuinely powerful. They’re just not a substitute for knowing your customers.